Here is a cool story about persevering in a Brown Bear hunt..

The words of the old shaman echoed in my ears: "To find your bear you must go until you see the reindeer and the water runs uphill." I had seen these things on the 86th day of a five-year odyssey in search of a brown bear and now, on the 89th, a red arrow appeared on the snow-covered mountain. The arrow pointed to a bear. This sign was not the shaman's magic, it was the blood of a another Kodiak giant slain by a mighty blow from the paw of the monster I was stalking.

As I climbed the mountain, I reflected on the trail that led me there. It had crossed the green jungles of Prince William Sound, the wind swept peninsula, snow fields that buried the trees and led finally to the heart of Kodiak Island. On the way it passed a legendary man and the daily lives of the great bears I had come to admire and respect more than any game I have hunted, except the elephant.

From the outside, the Alaskan coast was beautiful. From the inside, it became a cold, wet, green hell. The "little hike" to camp took four hours. The bogs, sleet, devil's club and lack of visibility made me wonder what I had done to myself. Ten days later, after seeing no bears, I was sure I had attempted suicide. Once, in the midst of the torment, I had seen a track made by something very large. The huge print spoke volumes about what I was pursuing. If I lived through the learning curve at the hands of Ed, an old sourdough guide, this was going to be a lot of fun.

Ed invited me back the following spring to try again. The jungle was still there, but we hunted above the worst of it. The rivers, with slimy rock bottoms, were the only trails a man could attempt to walk on, but it was warm enough now that the baths caused by a misstep were just annoying, rather than life threatening. We saw a bear on the second day; she looked huge, but was not. However, because she was walking down the stream we were walking up, and she turned on the trail that led to the tent, and it was dark, I remember her and the woof she made in the deep dark spruce very well.

Two days later I saw my first shootable bear. We were high, where the goats wintered, and where an avalanche might have killed one. Ed had taken several good bears off these winter kills, but the first bear I saw there was not a brownie. I did not understand why the big black bear continually looked back over his shoulder while he loped around the face of the mountain; Ed did.

"Keep watching, he ain't looking back for nothing." Ten minutes later a huge brown bear appeared. He had his head down, snuffling along the black bear's trail just like a hound. I asked Ed why. "If he can get close, he will kill him and eat him."

"Is it a big fight?" I wondered.

"No. I've seen brownies kill black bears twice. It's just like a big dog and a rat. One good shake and it's all over." The big bear paused to play with a piece of goat hide, losing interest in the black. "He's a good one, worth a try," Ed said. "But we won't be able to see when we get up there, the brush is too tall. You go up the slide, and I'll stay here where I can see. I can direct you to him once you get close." It looked like a clear plan to me, one that clouded a little as I shed my pack and picked up my rifle. "Be careful, he's hungry, looking for meat . . . you will do! If you hear me shoot, look behind you real fast." I guess I knew all along this was not a deer hunt.

I climbed as fast as I could, racing the fading light. When I was high enough to be level with the bear, fog rolled in. I could not see my feet and knew Ed could not see me nor the bear. Spooky was not an adequate word. I went down, looking over my shoulder, feeling an uneasy kinship with the black bear. I would need only half a shake. At sunrise the next morning the old bear was gone, and with him went my interest in wading up and down slippery rivers. It was time for a change of plans.

This trip used the big-time approach. A booking agent, a big, famous hunting outfit and the big, wide-open Alaska Peninsula should change my luck. It appeared they had when we needed to chase a medium-sized bear off the strip before the Cessna could land, but hopes and dreams slid downhill from there. The hunt turned out to be a disaster, a ripoff. Two other hunters had used the camp before me, and the outfit had several other camps nearby. Brown bears, at least the nine-foot-plus kind I was looking for, do not like company. I saw two bears in two weeks, not enough to make a hunt, but enough to pique my interest.

One of them showed me the true magnificence of the great brown bear. We saw him from about a mile away, high on a snow-covered ridge that led right to our feet. This was going to be easy. The bear was walking downhill, a sheer rock wall blocked his left, and a cornice of snow hung treacherously over the dizzy drop on his right. Unless he went back up, he had no choice except to walk into our laps. Or so I thought.

Just when I thought I had bears figured out and this one in shooting range, he walked over to the edge where the lip of snow was suspended in space. The brute looked over the edge and then began to bounce up and down on his front feet. He was thinking, testing the snow! He walked another 50 yards downhill, apparently not liking his first trail, and bounced again. This time the mountain caved beneath him. He vanished in the swirling white as the thunder of the distant avalanche reached my ears; but just as I began to feel sorry for him, the bear swam to the edge of the slide, shook off and sat down to watch the rest of the show from the sidelines. Then, he climbed back up and did it all over again!

I looked down at the old .416 Rigby in my lap and up at the great carnivore. He had the power and courage to use avalanches as a playpen, avalanches that kill men as if they were mice under the feet of elephants. I knew then that no man was his equal and wondered if any were worthy of possession of his soul.

A year later the plan became radical. Another guide friend adopted my cause and led me into the mountains above Prince William Sound, early in the spring of record snow. We traveled in a Super Cub with skis, camped in a two-man tent and prospected on mountaineering skis and snowshoes. I had a fantasy with a big bear far below and the wily hunter swishing down on him. My friend thought the bear would like the hunt, greeting me with open arms and mouth. We saw lots of sows and cubs, played in a winter wonderland where avalanche-death lurked at every step but did not find a big boar, which was the object of the hunt.

After failing on the ski-hunt, I was not sure where to turn; then a year after the fact, that terrible hunt on the peninsula did change my luck. A guide I met there phoned to basically apologize, not for himself but for the profession. He said he knew I had been ripped off and said he would like to offer me the chance to see the good side of Alaskan outfitters. Gary Thompson invited me to come to Kodiak Island, to the Pinell and Talifson camp on Olga Bay, the most successful and famous brown bear outfitters, and place, in the world. The invitation was not one of free price, but of opportunity. Hunters wait for years just for the chance to hunt there. A cancellation moved me to the front of the line.

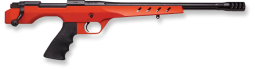

With this change of hunting territories came a change in rifles and bear rifle philosophy also. Previously the old Rigby .416 had been the answer to all bear-rifle questions. The rifle had been a great friend and security blanket in Africa and had been lucky enough to take my first big bull elk. Heretofore I had believed in the conventional wisdom that bear rifles had to be heavies, fighting rifles if you will. Therefore the Rigby was the obvious choice because it was big, powerful and lucky. However, as the days, weeks and years of bear hunting wore on and as my exposure to real bear hunters and their rifles grew, a lesson began to take shape. Many of the working bear guides carried .338 Winchesters as their backup rifles.

Bill Pinell and Morris Talifson had made careers with .375s, and no men had dealt with more or larger bears. Finally, there was the reality that the largest bear I would possibly encounter was going to be about half as large as a Cape buffalo, or one-twelfth the size of a good bull elephant. Finally, if you toss in the practicality that it is far more likely to attack a bear at 150 yards than 15, you realize a heavy is the wrong rifle for bear hunting. It was time to shed some weight and gain some range and precision.

I swapped from my favorite fighting rifle, the Rigby that weighed 101/2 pounds, to my favorite hunting rifle, a Champlin .340. It was exquisitely precise and had more than enough power for 1,000-pound critters. Besides, it was a full pound and a half lighter. On days that used every physical and mental fiber I possessed, those 24 ounces made a difference.

Bill Pinell and Morris Talifson moved into the old salmon cannery in the 1930s. They went there to trap and prospect. Soon they began to take people out to shoot the varmints that raided their garden, varmints that by any other name were Kodiak bears. Bill had passed away a few years earlier, but old Morris was still there. Sitting with him in the little cabin that had been his home for decades, I asked him about bears and bear rifles.

"Well, we started with a long-barreled .30-30 with a ladder sight. Good thing it had the sight; you needed to be a ways off cause it really made 'em mad. Then I got this three and six bits; she'll knock a bear down."

The "three and six bits" was an incredibly worn Winchester .375 H&H. The wood was worn away from the steel, and the Leupold scope had lost most of its black finish as well. Before me was one of the great, historic rifles of all time, and I was drinking whiskey with the man who had fought brown bears with it for more than 50 years! This must be brown-bear hunter's heaven.

Morris, how many bears? "You wouldn't believe me." Morris, how big did they used to get? "You wouldn't believe me." An hour later he produced an old black-and-white photo of two skulls next to a GI packboard. The skulls were as large as the board. How big, Morris? "Twelve feet," he said with profound certainty that ruled out any chance of exaggeration. And with a twinge of sadness more in his eyes than voice said, "There were real bears then." Tomorrow morning I was going to pack into a place where, at least in the past, bears weighed more than half a ton!

At last I was among them. We saw 20 bears in two weeks but none were shootable. Some were too small, others had badly rubbed fur. But not shooting did not bother me; just watching the bears was worth the price of admission. One shapeless brown spot in the snow stretched, yawned and stood to become an eight footer. He had been draped over an exposed rock, sound asleep in the sun. He was resting from a "big hunt" we would soon see repeated over and over again. Once awake the fellow scooped up a big ball of snow and rolled it down the mountain. After giving it a sporting head start, the young boar chased the rolling ball down and "killed" it. He was good for two of these "hunts" between naps.

Equally remarkable, but more serious, was the big, old sow with her tiny triplets. We watched her react to the scent of a boar, a boar that would make every effort to kill her cubs. She was apparently trapped in a box canyon, blocked by sheer rock walls hundreds of feet high. The old lady trailed the cubs to the wall and began to climb, the tiny balls of fur, with obvious reluctance, followed. When she reached the upper lip she pulled herself over the overhanging ice shelf and turned to coax the little ones. The first two scrambled over in her tracks, but the third was frightened. He seemed doomed as mom and the two cubs disappeared. Moments later the sow's head appeared over the lip as she slid on her belly, reached a huge paw over the edge and lifted the tiny cub. At that moment I wondered if I were worthy.

Gary said I was the worst case of bad-luck he had ever seen. It seemed reasonable that he would give up on finding me a bear, but he was more determined than ever. He had a plan for the next spring season, one that led into no man's land. We asked Morris about the bears there, and he said he had never wanted one badly enough to go that far. A pack that would kill an ordinary mortal had been a Sunday stroll for the old man in his younger times. He spoke of having to take a break, spend the night, on the 15-mile haul over two mountains - spend the night . . . if he had a 200-pound hide on his back. This was not going to be easy.

It began with a three-mile pack into our ordinary camp, followed by a raft ride six miles up the lake, a lake that had killed bear hunters before. Beyond lay 10 or more miles of bad ground: broken tundra much like half-buried Volkswagens and remnants of deep snow drifts. Every step was uphill. We were carrying almost 100 pounds each. This trek made a base camp at the very edge of nowhere. A broad valley separated several mountain ranges, snow sparkled everywhere above. This was easily as wild a place as I had ever been. Surely men had gone beyond, but it had been a long time.

We found what seemed to be the right bear on the second day, a huge dark boar that would go well past 10 feet with a hide that looked perfect. But during the last yards of the stalk he turned uphill, and we saw his back, a back rubbed in the den until it looked as if a lawnmower had cut a strip from nose to tail. He was a disappointment, but I had grown used to them. This was about the 50th bear that did not make the cut, and my days in the field, looking for the right one, just passed 80.

The wind, and where it took our scent, controlled the hunt. A tiny breeze, lifting our man-tainted air, could clear an entire valley of bears for days or weeks. When the wind was not perfect, we spent the days far out in the open flatlands, between the mountains, where we could watch but not risk contaminating the air. One day the bears offered a lesson in just how keen their noses were. A sow, with her cubs, was crossing the big open country when she seemed to bounce off a wall, then turned and ran for miles. The "wall" was our tracks made two days before, tracks made wearing rubber hip waders that had been cleansed by miles of pristine wilderness. Yet somehow her nose was able to define them as clearly as a real wall of concrete blocks that had been painted bright orange.

With her disappearance another day of wonder passed as did another night in a little two-man tent. Tonight we would eat, not because of time or habit, but because of need. We burned every calorie we could hold and then some. Sleep was also not the ordinary sleep of habit, but the sleep of dead-tired need. Brown bear hunting had become the most physically demanding and perhaps the most real thing I had ever done. This is what hunting must have been like before machines made men soft. I wondered every day if I were tough enough to continue, but here in this world there were many bears and many adventures. Any moment could hold the great confrontation. The expectation kept one foot moving in front of the other.

My visit to the shaman had only been a dream, at least in this life, but it began to take on spooky reality. One afternoon we crossed a little stream that made a sharp bend and clearly ran UP the hill, and by bizarre coincidence a herd of reindeer fed in the tundra beyond. I was tired again, perhaps too tired for now the lines between the dream and reality moved like mirage. I touched the water, and it was very cold and the ripples around my fingers demonstrated a flow that to every bit of reason was uphill. The reindeer shimmered in the distance, but they too were surely real. Dream or not, my superstition and exposure to real witch doctors made me believe we had, at last, gone far enough. The stream drained a big, complex valley.

The wind was wrong for two days. We dared not venture into the valley that began to seem forbidden. Instead, we watched from a knoll out in the tundra, watched in the late evening sunshine as an exodus began. Brown bears literally boiled out of the forbidden valley. Sows with cubs, one almost shootable nine-foot boar and several other miscellaneous bears loped out across the open spaces, headed for the mountains on the other side. It looked like the western movie where the women and kids run to hide. I was only about half serious when I said to Gary that it looked as if a bad gunfighter had come to town. He beamed back, "I think so."

The next morning the wind turned and gave us a chance to enter the valley, and there in the snow field, thousands of yards above, was the red arrow. At 50x the spotting scope revealed a head the size of an oil drum, in the snow, at the end of the arrow. The shaman had pointed to the bear. This was the gunfighter, and he was guarding the sow he had murdered the evening before. Her three, two-year-old cubs wandered aimlessly in the snow below.

It might have been easy, but there was deep snow between us and the bear, and we did not have snowshoes. Experience from days past told us that on a cool day the crust would soften and we would begin to fall through about 2:00 p.m. A warm day could move that time up by several hours. The bear probably would not move, he had meat; the temperature controlled the outcome. It was a dangerous gamble. If the snow held, I had a giant. If we floundered, fell through the shoulder-deep snow, a night in valley of the bears was going to be unpleasant . . . or worse.

We burned our lungs and legs, driving up the mountain wondering, at each step, when the snow would swallow us. A friendly cloud played in our favor, the snow held as we edged around the rim just below where the red arrow marked the bear. He was still there, mostly out of sight in a hole he dug to hold the dead sow. Gary howled like a wolf to bring the old warrior out into the open. He stood slowly, ready to defend his prize. As the rifle recoiled, placing the bullet on the center of his shoulder, I expected to see a roaring, snapping fury. Instead, he slid down the mountain in silent spirals.

He had the physique of a Sumo wrestler, forearms larger than my thighs, paws larger than my head. The tracks told of the old sow's fate. He had stalked her cubs, and she had turned to fight. There had been no struggle, her lower jaw was broken in three places, her skull crushed as if a truck had run over it. I know I was not worthy.

The words of the old shaman echoed in my ears: "To find your bear you must go until you see the reindeer and the water runs uphill." I had seen these things on the 86th day of a five-year odyssey in search of a brown bear and now, on the 89th, a red arrow appeared on the snow-covered mountain. The arrow pointed to a bear. This sign was not the shaman's magic, it was the blood of a another Kodiak giant slain by a mighty blow from the paw of the monster I was stalking.

As I climbed the mountain, I reflected on the trail that led me there. It had crossed the green jungles of Prince William Sound, the wind swept peninsula, snow fields that buried the trees and led finally to the heart of Kodiak Island. On the way it passed a legendary man and the daily lives of the great bears I had come to admire and respect more than any game I have hunted, except the elephant.

From the outside, the Alaskan coast was beautiful. From the inside, it became a cold, wet, green hell. The "little hike" to camp took four hours. The bogs, sleet, devil's club and lack of visibility made me wonder what I had done to myself. Ten days later, after seeing no bears, I was sure I had attempted suicide. Once, in the midst of the torment, I had seen a track made by something very large. The huge print spoke volumes about what I was pursuing. If I lived through the learning curve at the hands of Ed, an old sourdough guide, this was going to be a lot of fun.

Ed invited me back the following spring to try again. The jungle was still there, but we hunted above the worst of it. The rivers, with slimy rock bottoms, were the only trails a man could attempt to walk on, but it was warm enough now that the baths caused by a misstep were just annoying, rather than life threatening. We saw a bear on the second day; she looked huge, but was not. However, because she was walking down the stream we were walking up, and she turned on the trail that led to the tent, and it was dark, I remember her and the woof she made in the deep dark spruce very well.

Two days later I saw my first shootable bear. We were high, where the goats wintered, and where an avalanche might have killed one. Ed had taken several good bears off these winter kills, but the first bear I saw there was not a brownie. I did not understand why the big black bear continually looked back over his shoulder while he loped around the face of the mountain; Ed did.

"Keep watching, he ain't looking back for nothing." Ten minutes later a huge brown bear appeared. He had his head down, snuffling along the black bear's trail just like a hound. I asked Ed why. "If he can get close, he will kill him and eat him."

"Is it a big fight?" I wondered.

"No. I've seen brownies kill black bears twice. It's just like a big dog and a rat. One good shake and it's all over." The big bear paused to play with a piece of goat hide, losing interest in the black. "He's a good one, worth a try," Ed said. "But we won't be able to see when we get up there, the brush is too tall. You go up the slide, and I'll stay here where I can see. I can direct you to him once you get close." It looked like a clear plan to me, one that clouded a little as I shed my pack and picked up my rifle. "Be careful, he's hungry, looking for meat . . . you will do! If you hear me shoot, look behind you real fast." I guess I knew all along this was not a deer hunt.

I climbed as fast as I could, racing the fading light. When I was high enough to be level with the bear, fog rolled in. I could not see my feet and knew Ed could not see me nor the bear. Spooky was not an adequate word. I went down, looking over my shoulder, feeling an uneasy kinship with the black bear. I would need only half a shake. At sunrise the next morning the old bear was gone, and with him went my interest in wading up and down slippery rivers. It was time for a change of plans.

This trip used the big-time approach. A booking agent, a big, famous hunting outfit and the big, wide-open Alaska Peninsula should change my luck. It appeared they had when we needed to chase a medium-sized bear off the strip before the Cessna could land, but hopes and dreams slid downhill from there. The hunt turned out to be a disaster, a ripoff. Two other hunters had used the camp before me, and the outfit had several other camps nearby. Brown bears, at least the nine-foot-plus kind I was looking for, do not like company. I saw two bears in two weeks, not enough to make a hunt, but enough to pique my interest.

One of them showed me the true magnificence of the great brown bear. We saw him from about a mile away, high on a snow-covered ridge that led right to our feet. This was going to be easy. The bear was walking downhill, a sheer rock wall blocked his left, and a cornice of snow hung treacherously over the dizzy drop on his right. Unless he went back up, he had no choice except to walk into our laps. Or so I thought.

Just when I thought I had bears figured out and this one in shooting range, he walked over to the edge where the lip of snow was suspended in space. The brute looked over the edge and then began to bounce up and down on his front feet. He was thinking, testing the snow! He walked another 50 yards downhill, apparently not liking his first trail, and bounced again. This time the mountain caved beneath him. He vanished in the swirling white as the thunder of the distant avalanche reached my ears; but just as I began to feel sorry for him, the bear swam to the edge of the slide, shook off and sat down to watch the rest of the show from the sidelines. Then, he climbed back up and did it all over again!

I looked down at the old .416 Rigby in my lap and up at the great carnivore. He had the power and courage to use avalanches as a playpen, avalanches that kill men as if they were mice under the feet of elephants. I knew then that no man was his equal and wondered if any were worthy of possession of his soul.

A year later the plan became radical. Another guide friend adopted my cause and led me into the mountains above Prince William Sound, early in the spring of record snow. We traveled in a Super Cub with skis, camped in a two-man tent and prospected on mountaineering skis and snowshoes. I had a fantasy with a big bear far below and the wily hunter swishing down on him. My friend thought the bear would like the hunt, greeting me with open arms and mouth. We saw lots of sows and cubs, played in a winter wonderland where avalanche-death lurked at every step but did not find a big boar, which was the object of the hunt.

After failing on the ski-hunt, I was not sure where to turn; then a year after the fact, that terrible hunt on the peninsula did change my luck. A guide I met there phoned to basically apologize, not for himself but for the profession. He said he knew I had been ripped off and said he would like to offer me the chance to see the good side of Alaskan outfitters. Gary Thompson invited me to come to Kodiak Island, to the Pinell and Talifson camp on Olga Bay, the most successful and famous brown bear outfitters, and place, in the world. The invitation was not one of free price, but of opportunity. Hunters wait for years just for the chance to hunt there. A cancellation moved me to the front of the line.

With this change of hunting territories came a change in rifles and bear rifle philosophy also. Previously the old Rigby .416 had been the answer to all bear-rifle questions. The rifle had been a great friend and security blanket in Africa and had been lucky enough to take my first big bull elk. Heretofore I had believed in the conventional wisdom that bear rifles had to be heavies, fighting rifles if you will. Therefore the Rigby was the obvious choice because it was big, powerful and lucky. However, as the days, weeks and years of bear hunting wore on and as my exposure to real bear hunters and their rifles grew, a lesson began to take shape. Many of the working bear guides carried .338 Winchesters as their backup rifles.

Bill Pinell and Morris Talifson had made careers with .375s, and no men had dealt with more or larger bears. Finally, there was the reality that the largest bear I would possibly encounter was going to be about half as large as a Cape buffalo, or one-twelfth the size of a good bull elephant. Finally, if you toss in the practicality that it is far more likely to attack a bear at 150 yards than 15, you realize a heavy is the wrong rifle for bear hunting. It was time to shed some weight and gain some range and precision.

I swapped from my favorite fighting rifle, the Rigby that weighed 101/2 pounds, to my favorite hunting rifle, a Champlin .340. It was exquisitely precise and had more than enough power for 1,000-pound critters. Besides, it was a full pound and a half lighter. On days that used every physical and mental fiber I possessed, those 24 ounces made a difference.

Bill Pinell and Morris Talifson moved into the old salmon cannery in the 1930s. They went there to trap and prospect. Soon they began to take people out to shoot the varmints that raided their garden, varmints that by any other name were Kodiak bears. Bill had passed away a few years earlier, but old Morris was still there. Sitting with him in the little cabin that had been his home for decades, I asked him about bears and bear rifles.

"Well, we started with a long-barreled .30-30 with a ladder sight. Good thing it had the sight; you needed to be a ways off cause it really made 'em mad. Then I got this three and six bits; she'll knock a bear down."

The "three and six bits" was an incredibly worn Winchester .375 H&H. The wood was worn away from the steel, and the Leupold scope had lost most of its black finish as well. Before me was one of the great, historic rifles of all time, and I was drinking whiskey with the man who had fought brown bears with it for more than 50 years! This must be brown-bear hunter's heaven.

Morris, how many bears? "You wouldn't believe me." Morris, how big did they used to get? "You wouldn't believe me." An hour later he produced an old black-and-white photo of two skulls next to a GI packboard. The skulls were as large as the board. How big, Morris? "Twelve feet," he said with profound certainty that ruled out any chance of exaggeration. And with a twinge of sadness more in his eyes than voice said, "There were real bears then." Tomorrow morning I was going to pack into a place where, at least in the past, bears weighed more than half a ton!

At last I was among them. We saw 20 bears in two weeks but none were shootable. Some were too small, others had badly rubbed fur. But not shooting did not bother me; just watching the bears was worth the price of admission. One shapeless brown spot in the snow stretched, yawned and stood to become an eight footer. He had been draped over an exposed rock, sound asleep in the sun. He was resting from a "big hunt" we would soon see repeated over and over again. Once awake the fellow scooped up a big ball of snow and rolled it down the mountain. After giving it a sporting head start, the young boar chased the rolling ball down and "killed" it. He was good for two of these "hunts" between naps.

Equally remarkable, but more serious, was the big, old sow with her tiny triplets. We watched her react to the scent of a boar, a boar that would make every effort to kill her cubs. She was apparently trapped in a box canyon, blocked by sheer rock walls hundreds of feet high. The old lady trailed the cubs to the wall and began to climb, the tiny balls of fur, with obvious reluctance, followed. When she reached the upper lip she pulled herself over the overhanging ice shelf and turned to coax the little ones. The first two scrambled over in her tracks, but the third was frightened. He seemed doomed as mom and the two cubs disappeared. Moments later the sow's head appeared over the lip as she slid on her belly, reached a huge paw over the edge and lifted the tiny cub. At that moment I wondered if I were worthy.

Gary said I was the worst case of bad-luck he had ever seen. It seemed reasonable that he would give up on finding me a bear, but he was more determined than ever. He had a plan for the next spring season, one that led into no man's land. We asked Morris about the bears there, and he said he had never wanted one badly enough to go that far. A pack that would kill an ordinary mortal had been a Sunday stroll for the old man in his younger times. He spoke of having to take a break, spend the night, on the 15-mile haul over two mountains - spend the night . . . if he had a 200-pound hide on his back. This was not going to be easy.

It began with a three-mile pack into our ordinary camp, followed by a raft ride six miles up the lake, a lake that had killed bear hunters before. Beyond lay 10 or more miles of bad ground: broken tundra much like half-buried Volkswagens and remnants of deep snow drifts. Every step was uphill. We were carrying almost 100 pounds each. This trek made a base camp at the very edge of nowhere. A broad valley separated several mountain ranges, snow sparkled everywhere above. This was easily as wild a place as I had ever been. Surely men had gone beyond, but it had been a long time.

We found what seemed to be the right bear on the second day, a huge dark boar that would go well past 10 feet with a hide that looked perfect. But during the last yards of the stalk he turned uphill, and we saw his back, a back rubbed in the den until it looked as if a lawnmower had cut a strip from nose to tail. He was a disappointment, but I had grown used to them. This was about the 50th bear that did not make the cut, and my days in the field, looking for the right one, just passed 80.

The wind, and where it took our scent, controlled the hunt. A tiny breeze, lifting our man-tainted air, could clear an entire valley of bears for days or weeks. When the wind was not perfect, we spent the days far out in the open flatlands, between the mountains, where we could watch but not risk contaminating the air. One day the bears offered a lesson in just how keen their noses were. A sow, with her cubs, was crossing the big open country when she seemed to bounce off a wall, then turned and ran for miles. The "wall" was our tracks made two days before, tracks made wearing rubber hip waders that had been cleansed by miles of pristine wilderness. Yet somehow her nose was able to define them as clearly as a real wall of concrete blocks that had been painted bright orange.

With her disappearance another day of wonder passed as did another night in a little two-man tent. Tonight we would eat, not because of time or habit, but because of need. We burned every calorie we could hold and then some. Sleep was also not the ordinary sleep of habit, but the sleep of dead-tired need. Brown bear hunting had become the most physically demanding and perhaps the most real thing I had ever done. This is what hunting must have been like before machines made men soft. I wondered every day if I were tough enough to continue, but here in this world there were many bears and many adventures. Any moment could hold the great confrontation. The expectation kept one foot moving in front of the other.

My visit to the shaman had only been a dream, at least in this life, but it began to take on spooky reality. One afternoon we crossed a little stream that made a sharp bend and clearly ran UP the hill, and by bizarre coincidence a herd of reindeer fed in the tundra beyond. I was tired again, perhaps too tired for now the lines between the dream and reality moved like mirage. I touched the water, and it was very cold and the ripples around my fingers demonstrated a flow that to every bit of reason was uphill. The reindeer shimmered in the distance, but they too were surely real. Dream or not, my superstition and exposure to real witch doctors made me believe we had, at last, gone far enough. The stream drained a big, complex valley.

The wind was wrong for two days. We dared not venture into the valley that began to seem forbidden. Instead, we watched from a knoll out in the tundra, watched in the late evening sunshine as an exodus began. Brown bears literally boiled out of the forbidden valley. Sows with cubs, one almost shootable nine-foot boar and several other miscellaneous bears loped out across the open spaces, headed for the mountains on the other side. It looked like the western movie where the women and kids run to hide. I was only about half serious when I said to Gary that it looked as if a bad gunfighter had come to town. He beamed back, "I think so."

The next morning the wind turned and gave us a chance to enter the valley, and there in the snow field, thousands of yards above, was the red arrow. At 50x the spotting scope revealed a head the size of an oil drum, in the snow, at the end of the arrow. The shaman had pointed to the bear. This was the gunfighter, and he was guarding the sow he had murdered the evening before. Her three, two-year-old cubs wandered aimlessly in the snow below.

It might have been easy, but there was deep snow between us and the bear, and we did not have snowshoes. Experience from days past told us that on a cool day the crust would soften and we would begin to fall through about 2:00 p.m. A warm day could move that time up by several hours. The bear probably would not move, he had meat; the temperature controlled the outcome. It was a dangerous gamble. If the snow held, I had a giant. If we floundered, fell through the shoulder-deep snow, a night in valley of the bears was going to be unpleasant . . . or worse.

We burned our lungs and legs, driving up the mountain wondering, at each step, when the snow would swallow us. A friendly cloud played in our favor, the snow held as we edged around the rim just below where the red arrow marked the bear. He was still there, mostly out of sight in a hole he dug to hold the dead sow. Gary howled like a wolf to bring the old warrior out into the open. He stood slowly, ready to defend his prize. As the rifle recoiled, placing the bullet on the center of his shoulder, I expected to see a roaring, snapping fury. Instead, he slid down the mountain in silent spirals.

He had the physique of a Sumo wrestler, forearms larger than my thighs, paws larger than my head. The tracks told of the old sow's fate. He had stalked her cubs, and she had turned to fight. There had been no struggle, her lower jaw was broken in three places, her skull crushed as if a truck had run over it. I know I was not worthy.